Recently, Glynn Young and I were discussing Dancing Prince, the last book in his Dancing Priest series, and we talked about the sometimes-thin line between fiction and memoir.

Maclean did not write this story until he was in his 70s. Then it should follow that writing fiction must also help us. There is this idea that reading fiction helps us. And yet what he finds in the telling is Mystery. I think that is why Maclean wrote this story, to understand. It is those we live with and love and should know who elude us.” Only then will you understand what happened and why. Then he asked, “After you have finished your true stories sometime, why don’t you make up a story and the people to go with it? You like to tell true stories, don’t you?” asked, and I answered, “Yes, I like to tell stories that are true.” The line between memoir and fiction is no more clear than the the sentence that begins the book - “In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing.” The narrator is Norman, who also had a brother named Paul and a father who was a Scottish Presbyterian minister. Perhaps because this book reads like memoir. It was considered for the Pulitzer Prize in 1977, but no prize was awarded that year.

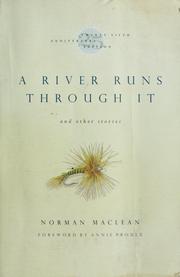

It was published as fiction, the first fiction title ever released by University of Chicago Press, where Norman Maclean spent his career.

In a 1981 Esquire profile of Maclean, Paul Dexter wrote of A River Runs Through It, “It is the truest story I ever read it might be the best written.” His poems “most often take place on a mountainside, a riverbank, or a roadside-‘near an exit.’” On the very first page of this novella, we learn the story takes place at the “junction of great trout rivers.” William Stafford, the poet who wrote A Ritual to Read to Each Other, our poem guide since 2020 dawned, was a poet of the American West. This is the copy I own, with wood engravings by Barry Moser.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)